Unemployment continues to be one of South Africa’s most critical economic and social issues. Over the past two decades, it has also been one of the country’s most difficult policy challenges, with numerous interventions failing to have a significant impact.

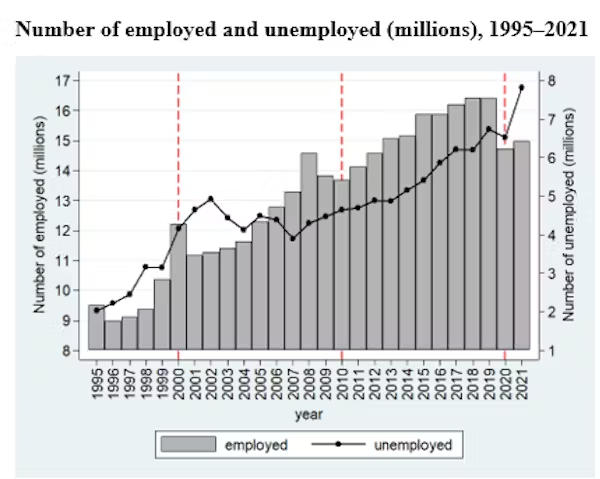

While the early post-apartheid years saw notable employment growth, this slowed after 2009. Both the unemployment rate and the number of unemployed individuals have risen sharply. According to the 2021 second quarter Quarterly Labour Force Survey, unemployment reached 7.83 million, with the rate climbing to 34.4%, the highest recorded since the survey began in 2008.

High unemployment is linked to various social problems, including crime, poor health, and even political instability. The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened the situation in the short term.

Two policy solutions often discussed are improving skills and liberalizing the labor market, though neither has been fully implemented. This is because South Africa’s structural unemployment is a complex issue with multiple causes.

Our research, presented at the 2021 Economic Society of South Africa Research Conference, sheds light on the issue. By analyzing unemployment trends from 2009 to 2019 using data from the Quarterly Labour Force Survey, we examined the problem through demographic, geographic, and industry-specific lenses. This allowed us to indirectly assess the effectiveness of employment strategies over the past decade.

Key Findings

Long-term labor market trends reveal a clear pattern. Employment grew more rapidly in the first decade of the 2000s than in the second. Unemployment began decreasing in 2003 but started rising again just before the global recession of 2008/9.

The relatively high growth period from 2000-2007 saw a reduction in the absolute number of unemployed, reaching its lowest point in the second half of 2007 (3.9 million). However, unemployment steadily increased throughout most of the following decade (2009-2019).

The data also shows a drop in employment after the 2008/9 recession, with subsequent job growth remaining limited compared to the earlier decade.

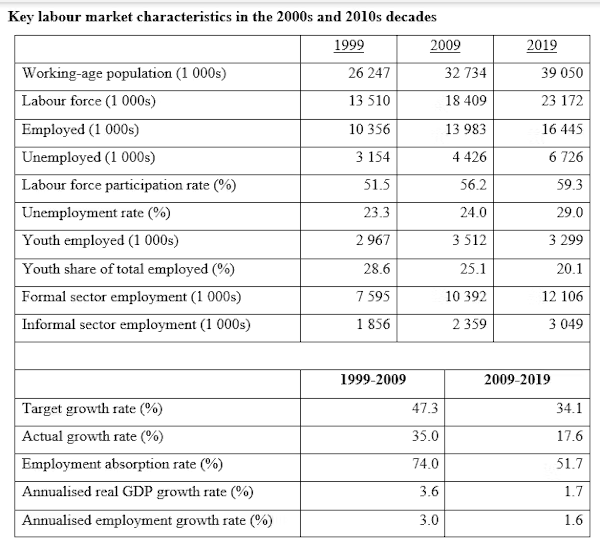

The table compares labor market statistics across three time periods: 1999, 2009, and 2019. It highlights a significant difference in employment growth rates, with a 35% increase during the earlier decade (1999-2009) compared to just 18% in the more recent decade (2009-2019). Alongside the faster rise in labor participation rates during 2009-2019, unemployment surged sharply—growing by 52% compared to 40% in the prior decade.

One notable trend is the decline in the youth’s share of total employment, which dropped by 7.5 percentage points from 28.6% to 20.1% over the two decades. In absolute terms, the number of employed youth also fell between 2009 and 2019. Several factors may explain this decline, but one particularly worrying trend is the increase in young people not engaged in education, employment, or training.

The target growth rate estimates the rate of employment growth required to absorb new entrants into the labor market over specific periods. The data shows that employment growth came closer to meeting this target between 1999-2009 compared to 2009-2019. The employment absorption rate, which compares actual growth to the target rate, reveals that in the most recent decade, employment growth was only half of what was needed to absorb new labor market entrants, whereas it was 74% during the previous decade.

Employment growth in the 2010s was more pronounced among Africans, males, people aged 35-54, residents of the Western Cape and Gauteng, those with at least a high school education, and employees in large companies with over 50 workers. The finance and community services sectors saw the largest employment and value-added growth, while manufacturing experienced a 1% decline, suggesting signs of de-industrialization in South Africa.

In terms of unemployment, the hardest-hit groups remain Africans, females, youth aged 15-34, individuals without a high school education, and residents of the Eastern Cape, Free State, and Mpumalanga. Two concerning trends emerged: 39% of unemployed individuals had never worked before, and the percentage of those unemployed for over five years increased from 24.1% in 2009 to 35.9% in 2019, suggesting a potential skills mismatch.

Looking ahead, skills development remains a major challenge for policymakers, with South Africa underperforming in global tests like TIMSS and SACMEQ, reflecting the low quality of education. This impacts people’s ability to develop skills later in life. Labor market reform is also contentious, with union power possibly contributing to high wages that disadvantage the unemployed.

Some argue that labor unions in South Africa have not had a severely negative impact on the economy, though wage formation and economic activity remain central to understanding labor market imbalances. The gap between training and employment opportunities is another area for potential policy improvement. While training programs could theoretically help prepare youth for the workforce, they have not led to substantial employment growth.

Small business development is often proposed as a solution, but research indicates that large firms have driven employment growth in South Africa. The country’s small informal sector reflects low levels of entrepreneurial activity.

Although a universal basic income (UBI) may not be fiscally feasible in the near future, the emergency income programs introduced during COVID-19 suggest its administrative viability. Some argue that structural barriers to low-skilled employment may be insurmountable, making UBI a potential, though politically unpopular, policy option. While UBI is often discussed in terms of poverty alleviation, its practical economic feasibility has yet to be thoroughly tested.